|

|

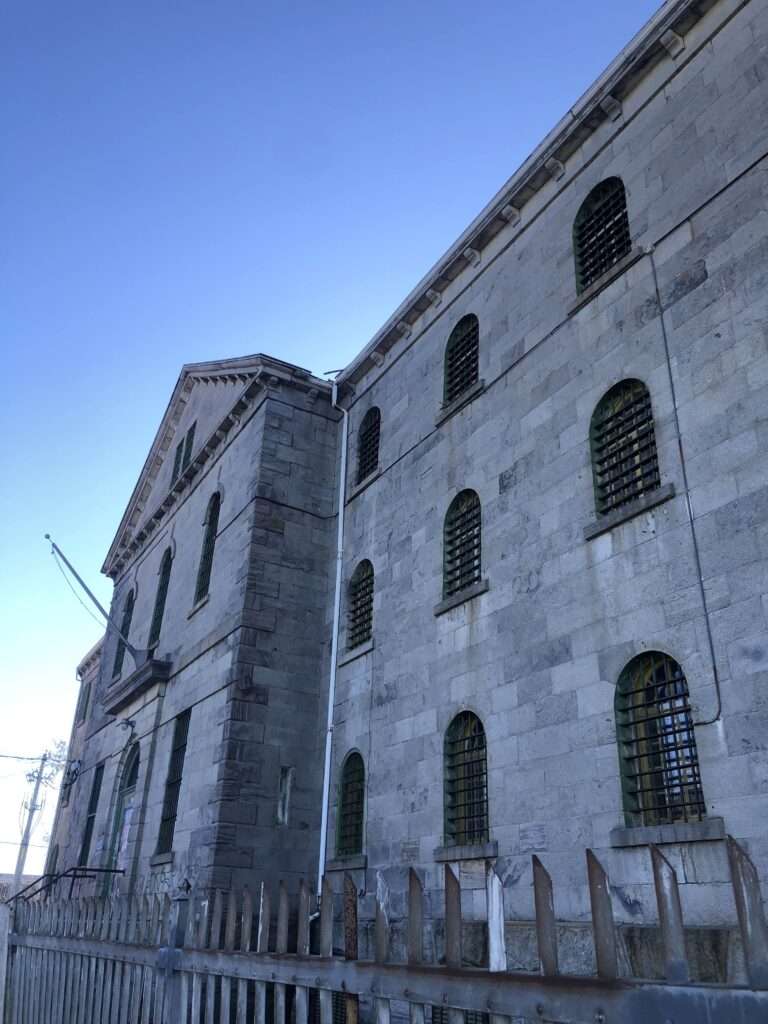

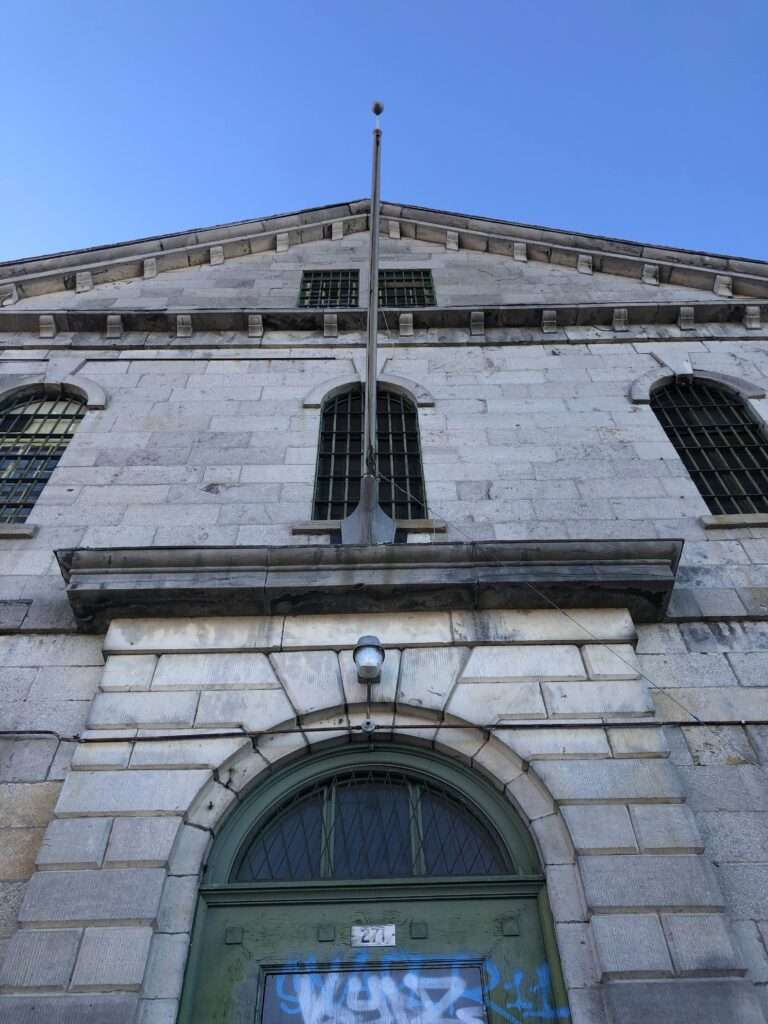

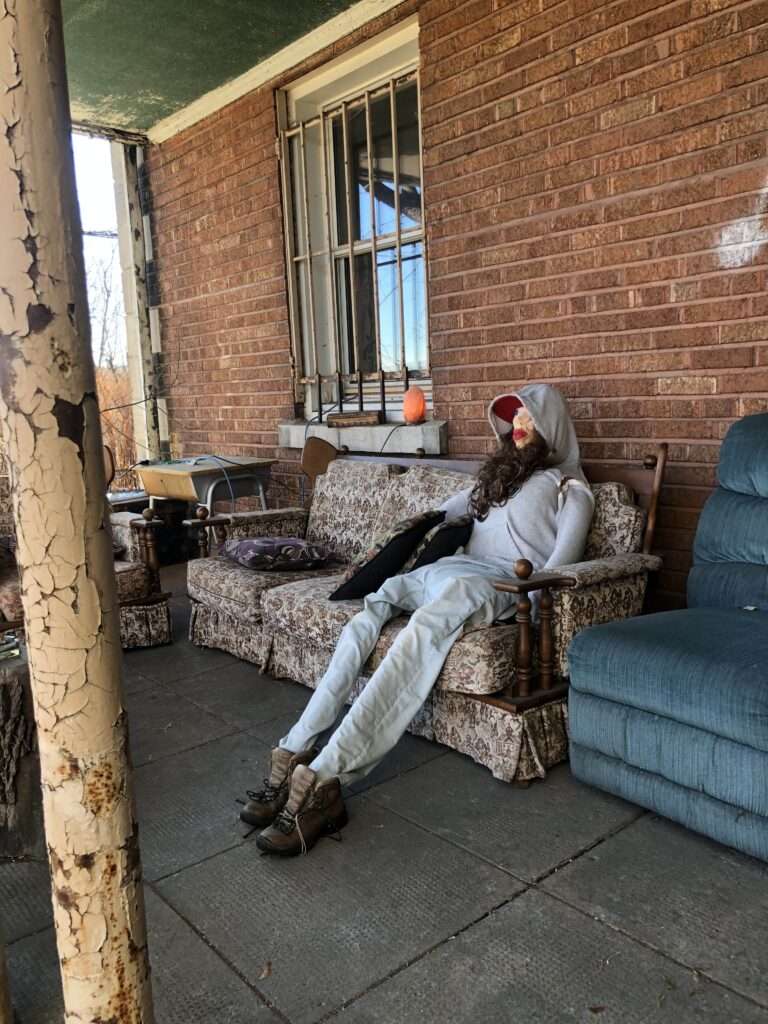

Many are familiar with Les Chutes de Magog, one of the most picturesque parts of the city. Looking from Rue Dufferin, you can get a magnificent view of the dam, the cliffs and rocks, and the huge volumes of water which flow through the Magog River. However, if you go through some of the side streets around this part of the city, you can find lesser known sites with very deep historical and cultural heritages. Passing over the Sentier de la centrale Frontenac onto Rue Cliff, you find nestled on a little corner what looks to be an old stone house. When I visited this place for the first time, I walked around this corner and found a front deck with tables, candles and a rocking chair with a strange mannequin sitting on it. Its face is painted in very bright colours with a grey outfit, sitting next to a brick with the word ‘executeur’ written on it. This is exactly when I knew there was more to this building than meets the eye at first glance. It turns out that the executor aspect is accurate. This place, the Sherbrooke Winter Prison, housed executioners and prisoners throughout its history. It has a deep, and often dark, past that many people may not be aware of just by looking at the mannequins, graffiti and boarded up windows. That deep dive into its history is something which I aim to do in this blog! I came across an excellent website Urbex Playground, a dedicated platform for enthusiasts of urban and rural photography, with a focus on exploring and capturing the beauty of abandoned, dilapidated, or forgotten places. The site aims to preserve the memory of locations that once held historical or cultural significance, even as they fall into neglect. Their research and photographs of the winter prison offered many more insights into the history of this prison. A Chilling Beginning To get a full picture, we have to start at the beginning of its existence, and the immediate roles it had in Sherbrooke. The Urbex Playground website notes that the prison was constructed in 1865 and was operational by 1870. It held 51 cells, including a small wing for women and a single isolation cell. Its walls have witnessed over a century of hardship, resilience, and tales of crime and punishment. The Winter Prison quickly earned a reputation as one of Quebec’s most brutal detention centers. Its architecture by Frederic Preston Rubidge hints at grandeur, though the suffering endured within these walls paints a more somber picture. The prison’s proximity to the courthouse district meant that justice and punishment loomed over the town in stark proximity to the daily lives of judges, lawyers, and residents. Its construction cost, which the Heritage Canada Foundation estimated at just over $30,000, speaks to the significance that the people of Sherbrooke placed on its role, although its later years saw both degradation and controversy. Crime, Punishment, and the Gallows The Winter Prison still evidences writing on its bricks that bear witness to the era of capital punishment in Canada, with six individuals meeting their end at the gallows here before the death penalty was abolished in 1976. Delving deeper into the Urbex site, I found that among the executed was Albert St-Pierre, convicted of murdering Reny Malloy, whose fate was sealed in 1932. Notably, the prison’s first execution, that of Bill Gray in 1879, involved portable gallows shared with neighbouring districts. Gray, who maintained his innocence to the end, was a tragic figure whose hanging became infamous as an early example of potentially wrongful conviction. His case highlights the limitations of justice at the time; he had been found with the victim’s belongings, yet his defense argued there was no proof the charred body found was indeed the victim’s. The hangman, a certain Radcliffe, was often criticized for his grimly inefficient technique, resulting in prolonged suffering. Stories circulated of prisoners lingering on the noose for twenty minutes, casting further shadows on the prison’s reputation and highlighting the stark realities of capital punishment. Three Stories of Notoriety: The Mégantic Outlaw, the Millionaire Murderer, and Unforgiving Family Ties Two notorious figures lend additional infamy to the prison’s story. Donald Morrison, known as the Megantic Outlaw, entered the Winter Prison after a long and dramatic manhunt. In 1887, Morrison, in an act of retaliation, shot and killed a bounty hunter over a family land dispute. With a bounty on his head, he evaded capture for two years before he was finally apprehended and held at the Winter Prison. Extra measures were taken to prevent his escape, but his sentence was ultimately served in the St. Vincent-de-Paul prison in Laval. Note: Among several sources, this story is told by Stanford, Richard (2003), At Any Price: The Story of the Megantic Outlaw, in the Beaver Canada’s History Magazine (October/November 2003). Harry K. Thaw, the “millionaire murderer,” brought international intrigue to the prison. He had been embroiled in a scandalous love triangle in New York City, where he shot his wife’s lover, artist Stanford White, during a Broadway show. Thaw’s wealth and status thrust his trial into the media spotlight, and after an insanity plea got him committed to an asylum, he made a daring escape across the Canadian border. Captured and temporarily housed at the Winter Prison, he was later extradited to the U.S. and eventually released. His presence at the Winter Prison brought a taste of international scandal to the small town. Inmates often faced mental and emotional trials as punishing as their physical confinement. Family members, too, bore the shame of association. One of the more tragic tales is that of Samuel Madeleine, who was sentenced for stealing a horse in Waterville. When his mother and sister came to visit him, they expressed disappointment and shame; it is said his mother told him she would have preferred to see him “six feet under rather than inside the penitentiary.” Madeleine took his own life soon after, a haunting reminder of the isolation and stigma prisoners faced. The Fall and Preservation of a Relic After over a century in operation, the prison closed its doors in 1990, and its inmates were transferred to modern facilities. The building was at risk of demolition when a local heritage group, the Société de sauvegarde de la vieille prison, intervened, purchasing the property for a symbolic dollar to preserve this piece of history. While parts of the prison briefly housed artists and community organizations, the majority has remained unoccupied. Years of neglect have taken their toll with deteriorating walls, leaking roofs, and high restoration costs deterring progress. It turns out that even as recently as 2007, there was talk of demolishing the Winter Prison Complex. The future of the site seemed uncertain due to its neglect. In April 2007, the Building Authority condemned the building because of its advanced state of disrepair. Winter Prison was ultimately saved from demolition by a group dedicated to its rehabilitation and continued use by the community. However, local groups often struggled under the high costs of maintenance and restoration, challenges that were especially burdensome for municipal and provincial properties of great heritage interest. Financial incentives from all levels of government were crucial to ensuring the viability of such significant architectural achievements, according to the Heritage Canada Foundation. On November 8, 2024, Quebec’s Minister of Culture and Communications, Mathieu Lacombe, announced the designation of the Prison as a heritage site. This has “listed” the building, allowing full preservation of the site for many more years to come. Through community perseverance and historical awareness, the prison may yet serve as a site of reflection and remembrance, immortalizing a past that, while dark, is inseparable from the fabric of Sherbrooke’s heritage. Daniel Kirchin is a writer who moved to Quebec in January from England, after studying French at University. Whilst here, he’s written about local topics, events, historical and cultural pieces surrounding the Eastern Townships. (Photos: Dan Kirchin) This blog would not have been possible without the invaluable contributions of several sources that shed light on the Winter Prison’s intricate history. Urbex Playground provided meticulous research and captivating visuals, bringing its haunting past to life. The Canadian Heritage Foundation and the National Trust for Canada offered essential insights into the architectural and cultural significance of the site, including its status as one of Canada’s most endangered places. Additionally, Richard Stanford’s article, “At Any Price: The Story of the Megantic Outlaw,” published in The Beaver: Canada’s History Magazine, provided rich context on one of its most infamous inmates. Lastly, my thanks go to the Townships Sun for giving me this platform to explore and share this remarkable chapter of Sherbrooke’s history. Together, these resources have made it possible to honor the legacy of the Winter Prison. |

Sherbrooke has a hidden history that people don’t often see. Downtown are sites that hold deep and compelling histories. We often pass by them every day without further thought.

Sherbrooke has a hidden history that people don’t often see. Downtown are sites that hold deep and compelling histories. We often pass by them every day without further thought.