“Camp N” or “Camp 42” (i.e. prison), located beside what is now the Talbot Prison, bordering a well-travelled bike path along the St. Francis River in Sherbrooke. Prisoners walk back to their quarters in November 1945. The walkway connected two separate sections of the camp. — (Source: Dept. of National Defence, LAC PA-114463, POWsinCanada.ca)

“Camp N” or “Camp 42” (i.e. prison), located beside what is now the Talbot Prison, bordering a well-travelled bike path along the St. Francis River in Sherbrooke. Prisoners walk back to their quarters in November 1945. The walkway connected two separate sections of the camp. — (Source: Dept. of National Defence, LAC PA-114463, POWsinCanada.ca)

| Lost History of Jewish Refugees in Sherbrooke |

EVENT REVIEW by Mary Purkey

On Wednesday, Nov. 6, about 100 people attended a talk entitled “The Lost History of Jewish Refugees in Sherbrooke During World War II,” by Ian Darragh.

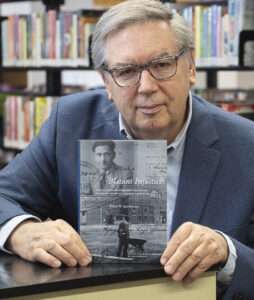

Mr. Darragh is former editor-in-chief of Canadian Geographic, and also editor of Blatant Injustice: The Story of a Jewish Refugee from Nazi Germany Imprisoned in Britain and Canada during World War II, the memoir of Walter W. Igersheimer.

That Canadian imprisonment was in Sherbrooke, Quebec.

Dr. Igersheimer fled Germany to Britain as a refugee before WWII, and was then interned as a potential “enemy alien” just as he graduated from university.

In its panic about infiltration of Britain by potential German spies, the British government rounded up 30,000 Jews who had fled Germany, and then discovered it could not manage so many “enemy aliens.” So the government shipped large numbers to Canada where many, Dr. Igersheimer among them, were interned in Camp N, a “camp” (i.e. prison) beside what is now the Talbot Prison, bordering a well-travelled bike path along the St. Francis River in Sherbrooke.

Mr. Darragh described life for these unfortunate human beings who had fled Nazism only to find themselves consigned to spending the war in this detention centre/prison in miserable, unsanitary conditions. They were dumped in a cold, dirty, and ill-equipped warehouse complex in two buildings, one of which still exists today at 1075 Talbot Street and is used for bus repairs. Three layers of barbed wire and armed guards separated them from the world. They lacked adequate food and any medical care at all.

Their uniforms had large red circles on the back (bulls eyes, Mr. Darragh said) to distinguish them. They were called “dirty Jews” and other anti-Semitic slurs by the camp officers.

It is ironic that most had wanted to join the fight against the Nazis, and many turned out to be brilliant in scientific fields (two Nobel laureates among them). They accomplished some amazing feats while interned, including the creation of a free university.

The story of their treatment does not do us proud. Apart from the small Jewish community that existed in Sherbrooke at the time and which quietly tried to assist the prisoners, most Sherbrookers knew nothing of this travesty, or if they did know, gave little thought to it. No one asked questions.

Even today, most of us have heard only the stories of a camp for German prisoners of war at Sherbrooke.* There is no monument or plaque (as exists in many European towns) to encourage us to remember these victims of war and prejudice. The lost history challenges us to reflect on the accusations we have heard about the wilful blindness and passivity of most Germans during World War II. How can we explain the failure of our own community to rise up on behalf of these victims of grievous and cruel violations of human rights and dignity? Doing so would have cost us nothing, in contrast to the price Germans paid for speaking out.

It makes one wonder: Who were we then? Who are we now?

November 6 was an auspicious time for this event. Donald Trump had just been elected president, with all his talk about ridding America of all the illegal migrants (In his words, “They’re bringing drugs, they’re bringing crime, they’re rapists…“) It is hard not to wonder how long it will take for detention facilities to be constructed in the US to facilitate deportations.

But then, what about refugees and migrants in our own country? Lives were broken and lost because of the internment of Jewish refugees by Britain and Canada during WW II. The talk on Wednesday evening was not only a historical lecture but a wake-up call. We fool ourselves if we imagine that such a thing cannot happen now, or that we too could not suffer from willful blindness and passivity.

Mr. Darragh’s talk provided shocking details about what can happen when humans are “othered” and forgotten. In examining the sad history of the 1930s and 40s, he also encouraged his audience to stand against injustice today, particularly in the treatment of those in our midst who come to us seeking protection from persecution.

*In fact, Camp N, as it was called, had two phases: from 1940-1942 it was a prison for civilian refugees. On Nov. 25, 1942, they were transferred to Camp I at Fort Lennox, QC. From Dec. 2, 1942 until it closed on July 14, 1946, Camp N in Sherbrooke imprisoned mainly German merchant marine sailors. (Source: email from Mr. Darragh)

The event on November 6, 2024, was supported by the Eastern Townships Resource Centre, Bishop’s University, the Bibliothèque Lennoxville Library, the Musée d’histoire de Sherbrooke, and the Lennoxville-Ascot Historical and Museum Society. A recording of the talk by Mr. Ian Darragh can be viewed on YouTube at “Lost History / L’histoire oubliée : Jewish Refugees in Sherbrooke, Québec during World War II.”

Blatant Injustice is published by McGill-Queen’s University Press (2024) and can be ordered at both Black Cat Books and Brome Lake Books. It is also available in paperback, e-book and audiobook at Indigo Books (online and in in-store); Amazon and Rakuten Kobo.

Mary Purkey wrote this review. Before retirement, she taught Humanities at Champlain College in Lennoxville for decades and while there, co-founded and co-coordinated the Bishop’s/Champlain Refugee Student Sponsorship Project. She has had a long affiliation with the Canadian Council for Refugees and is also co-founder and coordinator of the Mae Sot Education Project, a Lennoxville-based volunteer project that supports education for refugee and migrant youth from Myanmar in Thailand (maesoteducation.ca).

|

|

|

|

Water colour painted by an internee of the abandoned locomotive shed at Rue Talbot in Sherbrooke which housed the 800 refugees. Before the refugees made repairs, the roof leaked, the floor was coated with engine oil, and there were five cold water taps and six latrines for some 800 prisoners. There were no beds on their first nights in Camp N. (Credit: Library and Archives Canada/E1913624) |

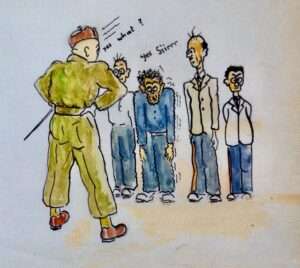

Caricature of Sergeant-Major Macintosh, the second-in-command of Camp N at Sherbrooke, Quebec, terrorizing internees. A former used-car salesman, Macintosh regularly subjected the internees to anti-Semitic slurs. (Image: Unknown internee artist/Library and Archives Canada/E-1913623)

|

© Townships Sun 2024

© Townships Sun 2024

Last revised: 5:06 pm 10 Nov ’24